Health solutions

We Provide High Quality Services

Problems

Vision disorders, including amblyopia, strabismus, and significant refractive errors, are the most prevalent disabling childhood conditions in the United States, one in four children have some form of vision problem.

An estimated 857,000 children in the United States are blind or have uncorrectable mild, moderate, or severe vision impairment.

Pediatric low vision is defined as irreversible vision loss or permanent visual impairment in a person younger than 21 years old, which cannot be improved with refractive correction, medical treatment, or surgical intervention. This condition can result in challenges with reaching developmental milestones, obstacles with achieving educational goals, difficulty with social interactions, and loss of independence.

In the pediatric population, low vision may be mistaken for intellectual disability and behavioral disorders, and may be masked by systemic health issues that obscure its diagnosis. Therefore, a keen understanding of how to detect and manage pediatric low-vision can have an important and lifelong impact on this vulnerable patient population.

Pediatric low vision may be due to a primary ocular structural abnormality, or secondary to other ocular pathology. It may develop as a result of a genetic disorder, or may occur as a result of cerebral visual impairment (CVI).

Vision and eye health problems among children:

Refractive error occurs when the irregular shape of the cornea, lens, or eyeball improperly focuses light on the retina, producing blurred vision that can be corrected through use of spectacles or contact lenses or through refractive surgery. Refractive errors, including hyperopia, myopia, astigmatism, and anisometropia, are the most common causes of vision impairment in children.

Amblyopia, sometimes called “lazy eye,” is a neurological disorder in which vision fails to develop in one or both eyes when the corresponding part of the brain “shuts off” in response to a lack of clear images from the eye. Amblyopia is the leading cause of vision loss in one eye in children, although good outcomes can be achieved with early diagnosis and treatment.[

Strabismus is a condition in which the eyes are incorrectly aligned, with one eye turning out or in or up or down and the other looking straight ahead.[4] Strabismus affects between 2.5% and 4.6% of children, but early diagnosis and treatment can prevent the development of amblyopia, particularly among preschool-aged children whose visual system is still developing.

Vision and eye health problems among children:

Refractive error occurs when the irregular shape of the cornea, lens, or eyeball improperly focuses light on the retina, producing blurred vision that can be corrected through use of spectacles or contact lenses or through refractive surgery. Refractive errors, including hyperopia, myopia, astigmatism, and anisometropia, are the most common causes of vision impairment in children.

Amblyopia, sometimes called “lazy eye,” is a neurological disorder in which vision fails to develop in one or both eyes when the corresponding part of the brain “shuts off” in response to a lack of clear images from the eye. Amblyopia is the leading cause of vision loss in one eye in children, although good outcomes can be achieved with early diagnosis and treatment.[

Strabismus is a condition in which the eyes are incorrectly aligned, with one eye turning out or in or up or down and the other looking straight ahead.[4] Strabismus affects between 2.5% and 4.6% of children, but early diagnosis and treatment can prevent the development of amblyopia, particularly among preschool-aged children whose visual system is still developing.

Signs of Low Vision in Children

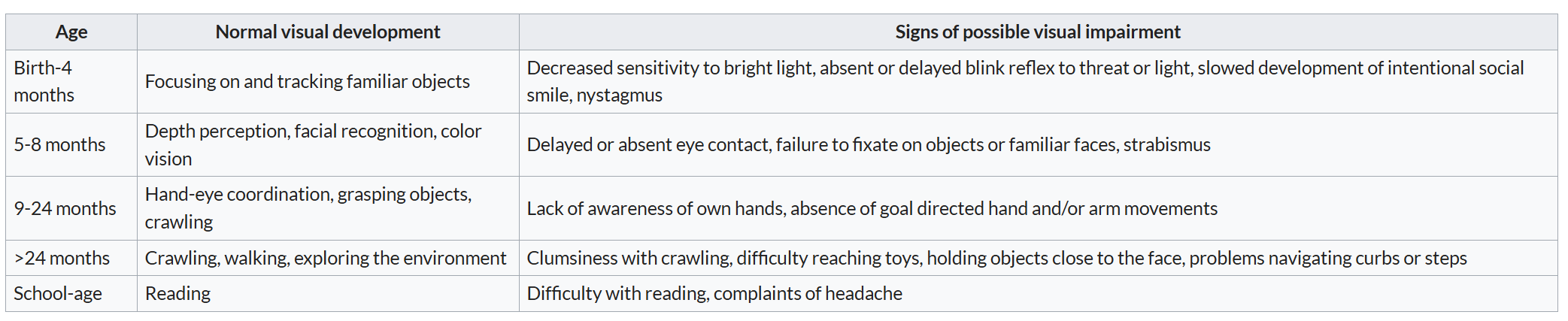

A child’s visual development is marked by specific milestones.

From birth to approximately four months of age, an infant begins adjusting to light and focusing on objects in front of them. From five to eight months depth perception and facial recognition become part of a child’s visual behavior. From nine to twelve months, babies begin to demonstrate hand-eye coordination and gross spatial recognition as they become mobile with crawling.[9] These skills build through the first two years of life allowing children to explore other objects of interest in their environment such as toys and foods. Knowing the key steps in normal visual development for each age group is therefore crucial in detecting early signs of delayed visual development.

There is well-documented evidence that gains in visual acuity, enhanced visual functioning, improved quality of life, and stronger academic performance in children can be achieved with appropriate and comprehensive low vision management. Furthermore, early intervention with low vision services is associated with improved outcomes compared to low vision support initiated at school age.

This Table outlines the signs of normal and delayed visual development according to a child’s age. Decreased sensitivity to bright lights, delayed or absent eye contact, slowed development of an intentional social smile, lack of awareness of an infant’s own hands, the absence of goal-directed hand movements, and failure to fixate on familiar objects such as toys and faces may all be warning signs to the parents and/or the pediatrician of low vision.

Evidence-Based Interventions and Strategies

Appropriately timed receipt of quality comprehensive eye care, including diagnosis, treatment, and management, can significantly reduce the impact of childhood vision and eye problems on individual children. According to the Institute of Medicine, “quality care must be safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered. A comprehensive eye examination by an optometrist or ophthalmologist is the gold standard of eye care. The Affordable Care Act identified pediatric vision care as an essential health benefit, increasing coverage of vision among children from birth to the age of 18 years in all qualified health plans to an annual comprehensive eye examination and materials benefit in almost all states.

Insurance coverage has been shown to correlate with improved vision and eye health outcomes and lower rates of vision impairment. Not all children have medical insurance, and for some cost sharing may make the cost of care prohibitive. In these cases, a number of charitable programs sponsored by professional societies, insurers, eyewear manufacturers, nonprofits, and others may help to close the gap. In addition, 90% of sports-related eye injuries can be prevented with the use of protective eyewear. The challenge, then, is ensuring that all children have access to quality eye care.

Data collection

The first step is to better define the problem. The limitations of existing epidemiological data on children’s vision and eye health, as well as their receipt of eye care, hamper the development of evidence-based clinical care and population health strategies.

Surveillance is one of the foundations of public health and the basis for policy-making and decision making. There are a variety of national health status and access surveys, including the National Survey of Children’s Health, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Robust use of these surveys to gather objective clinical data (including disability data) on children’s vision and eye health is crucial to the improvement of population health. If these surveys ask about children’s vision, it is usually a question about existing vision impairment or about “vision screening.”

None of the national surveys collect information on receipt of or access to comprehensive eye care that can be correlated with outcome data, but access to such information could substantially inform policy decisions at the federal, state, and local levels and help measure the success of interventions. Surveys could include such questions as “Has your child received a comprehensive eye examination from an eye doctor (optometrist or ophthalmologist) in the past 12 months?” Survey questions could also be adapted for use in surveys administered in schools or school systems, early childhood programs, or juvenile justice settings. Data on children’s vision care and eye health outcomes could potentially be paired with information on educational outcomes to provide greater support for the role of vision and eye health in learning.