Opinion

Virtual Visits in Ophthalmology:

Timely Advice for Implementation During the COVID-19 Public Health Crisis

Theodore Bowe, BS,¹ ² David G. Hunter, MD, PhD,¹–³

Iason S. Mantagos, MD, PhD,¹–³ Melanie Kazlas, MD,¹–³

Benjamin G. Jastrzembski, MD,¹–³ Eric D. Gaier, MD, PhD,¹–⁴

Gordon Massey, MBA, CRA,² Kristin Franz, MBA,²

Caitlin Schumann, MPH,⁵ Christina Brown, MS,⁵

Heather Meyers, MBA,⁵ and Ankoor S. Shah, MD, PhD¹–³,⁵

¹ Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

² Department of Ophthalmology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

³ Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

⁴ Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

⁵ Innovation and Digital Health Accelerator, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Abstract

Virtual visits (VVs) are necessitated due to the public health crisis and social distancing mandates due to COVID-19. However, these have been rare in ophthalmology. Over 3.5 years of conducting >350 ophthalmological VVs, our group has gained numerous insights into best practices. This communication shares these experiences with the medical community to support patient care during this difficult time and beyond. We highlight that mastering the technological platform of choice, optimizing lighting, camera positioning, and “eye contact,” being thoughtful and creative with the virtual eye examination, and ensuring good documenting and billing will make a successful and efficient VV. Moreover, we think these ideas will stimulate further VV creativity and expertise to be developed in ophthalmology and across medicine. This approach holds promise for increasing its adoption after the crisis has passed.

Keywords: telemedicine, telehealth, ophthalmology, COVID-19

Introduction

Virtual visits (VVs) decrease patient cost,¹ increase satisfaction,² ³ and allow ophthalmologists to care for patients efficiently.³ With massive disruptions in health care caused by COVID-19, interest in VVs…

for ophthalmology and across medicine is increasing.

Numerous national and state agencies recognize telehealth as vital during this emergency,⁴–⁷ lifting regulatory boundaries—such as allowing the use of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-non-compliant audiovisual platforms for VVs⁷—and adding temporary pay parity between in-person and telehealth visits. These measures aim to facilitate social distancing while maintaining access to health care.

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, we had already conducted hundreds of VVs dating back to 2016. This early experience led to an understanding of best practices that are transferable to other subspecialties beyond pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. We hope that sharing these best practices will be helpful to others and believe that this dialogue will spur innovation among colleagues.

Technological Platforms

We use a commercially available HIPAA-compliant platform that integrates with our scheduling software. This platform provides a virtual waiting room that scrolls through a series of customizable screens, which we use to inform patients of best practices to optimize their VV experience and their estimated wait time.

A disadvantage is that it requires patients to download software and access the virtual waiting room via a link sent by email. However, recent regulatory changes now allow ophthalmologists to use more prevalent and intuitive audiovisual platforms that are not HIPAA-compliant. While the use of these systems may need to cease after the state of emergency ends, in the interim, they can help providers deliver services more quickly.

Etiquette and Best Practices

Many interpersonal skills and procedures that providers have mastered in person do not translate intuitively to virtual encounters. Table 1 outlines best practices for VVs.

As with any medical appointment, it is essential to first obtain explicit permission to conduct the visit. This consent is typically built into commercial telehealth systems as a requisite for entry into the virtual waiting room. If an ad hoc system is used, informed consent must be manually obtained and documented.⁸

Second, providers must conduct visits in a private space with a professional backdrop and attire. They must also inform patients of all parties present on the provider’s side to respect and uphold patient privacy.

Third, virtual visits (VVs) are most successful when both audio and video feeds are of high quality. To optimize the video feed, the computer, tablet, or phone should be stabilized on a flat surface at eye level for both the provider and the patient. The patient should also be positioned stably—placing infants on laps and toddlers in highchairs works well.

Lighting is critical: the face should be well-lit with no backlighting. Natural light from windows is ideal. Adequate lighting benefits both the provider and patient—patients must be clearly visible for examination, and well-lit providers help convey nonverbal cues during conversation. Placing the patient’s video feed close to the camera or looking slightly below the camera during discussion also helps simulate eye contact.

Fourth, virtual examinations tend to be most effective in pediatric patients when completed at the start of the encounter—while the novelty of the virtual format still holds the child’s attention. History taking and counseling can then follow, once the child disengages from the screen.

Fifth, there are logistical advantages to scheduling VVs in dedicated time blocks at the beginning or end of the clinic day. This approach minimizes the cognitive load of “task-switching” between in-person and virtual encounters and reduces timing disruptions. Morning VVs also leave open the possibility of same-day in-person visits if any concerning findings arise.

Virtual Examination

Many providers express skepticism about whether an ophthalmic examination can be effectively conducted virtually. However, our experience suggests that—while not a substitute for all aspects of in-person care—thoughtfully designed virtual eye exams can yield valuable clinical insights.

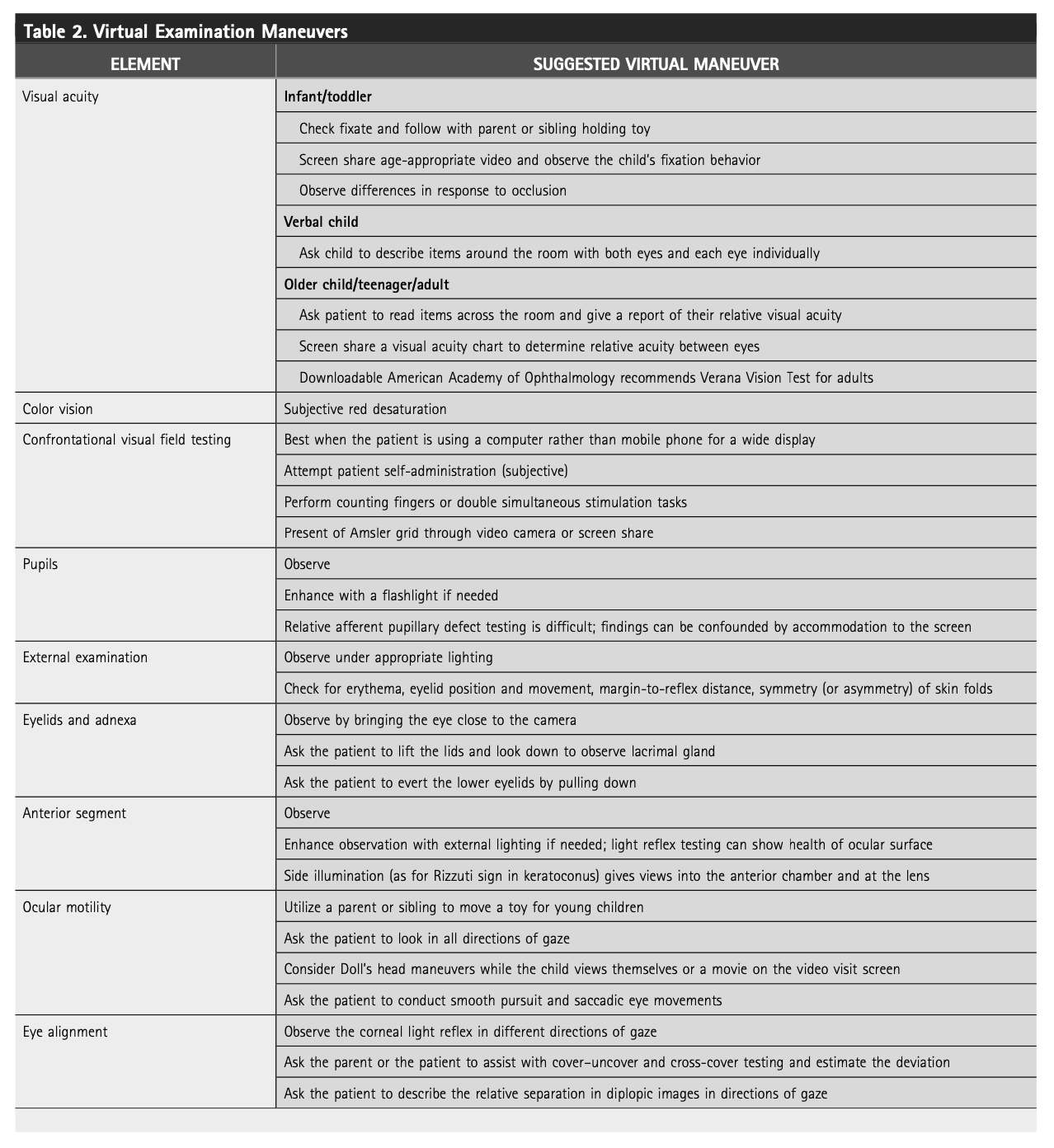

Our experience demonstrates that virtual visits (VVs) can yield valuable clinical information to support medical decision-making and patient counseling.³ Table 2 outlines several examination methods we have found effective; while not exhaustive, this list continues to evolve with ongoing experience.

Supplemental materials such as patient-submitted videos, photographs,⁹ and even home-based visual acuity assessments can further enhance the utility of virtual examinations. When the clinical history or examination findings raise concern or remain unclear, we maintain a low threshold for converting to a same-day in-person visit. This practice ensures that patient safety is never compromised, even when leveraging the convenience of virtual care.

Interestingly, the inherent limitations of virtual examinations can, in some cases, highlight the diagnostic power of a thorough clinical history. By emphasizing detailed history-taking, virtual visits may paradoxically enhance diagnostic accuracy when physical exam capabilities are constrained.

Documentation and Billing

Virtual visits (VVs) should be documented with the same rigor as in-person encounters, while clearly noting their inherent limitations. For instance, we include phrases such as “estimation via video observation during virtual visit” when describing components of the examination. Specific methods used should be detailed—e.g., “visual acuity in an infant: fixes and follows a toy moved side-to-side by parent.”

At the conclusion of each note, we include documentation that the visit was conducted virtually due to social distancing mandates. This includes the physical locations of both patient and provider, all individuals present during the visit, total duration, and the percentage of time spent in face-to-face counseling.

We bill these visits using standard Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) evaluation and management codes with the addition of the GT modifier to indicate a telehealth service. We strongly recommend coordinating with institutional billing and compliance teams to ensure alignment with current coding guidelines and payer policies.

Proposed Indications by Subspecialty

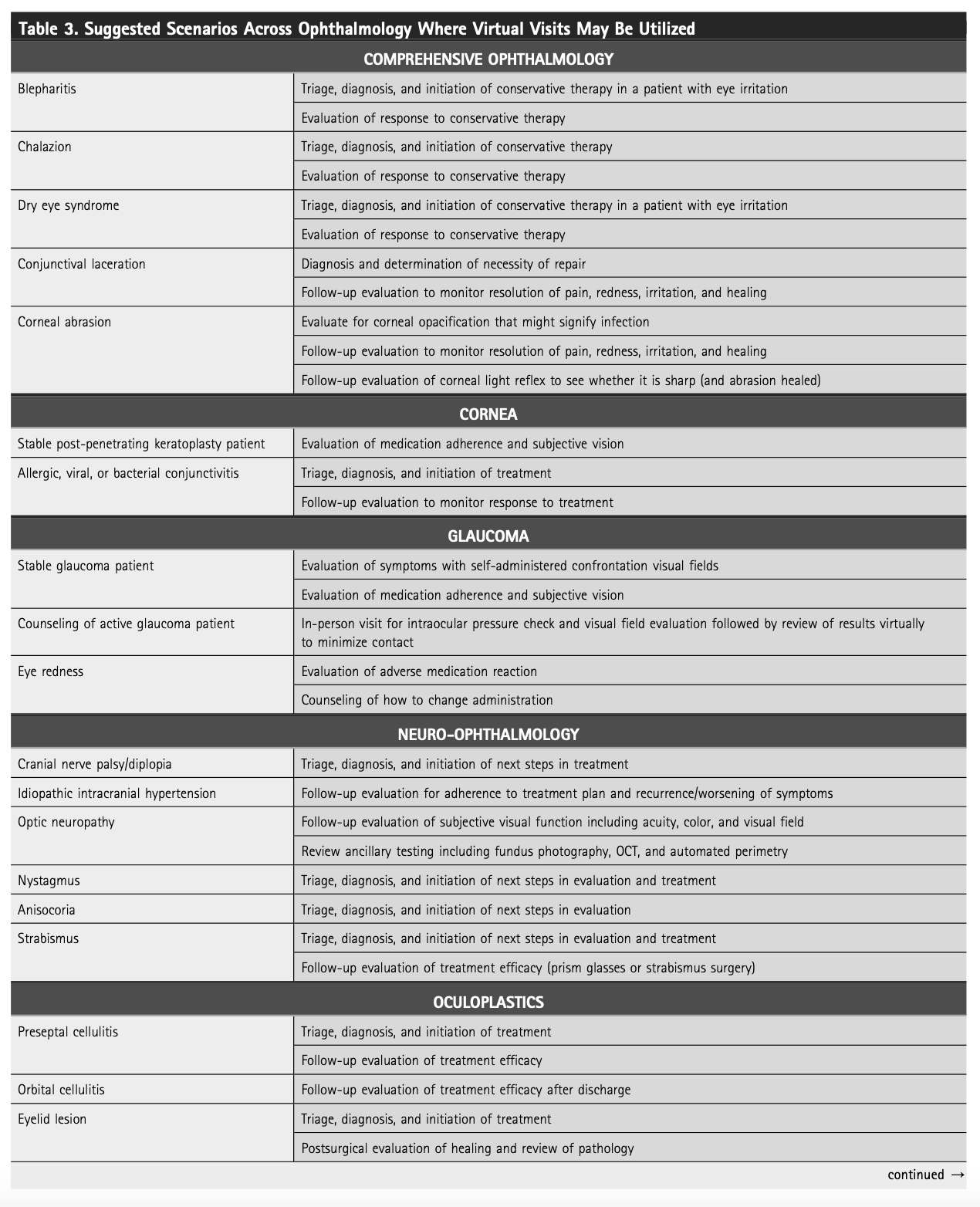

Our implementation of VVs has primarily occurred within pediatric ophthalmology and adult strabismus care; however, many of the best practices we’ve established are readily applicable to other ophthalmic subspecialties. Table 3 outlines potential indications by subspecialty, though this list is likely to expand as ocular telemedicine evolves.

In certain scenarios, a hybrid model may offer optimal efficiency and safety. For example, diagnostic testing may be performed in the clinic, with history-taking, result interpretation, and counseling delivered virtually. This strategy can reduce in-person exposure while maintaining comprehensive patient care.